Visitors to Arusha often used to say that it was difficult finding the home of naturalist and wildlife guide James Wolstencroft.

James lived with his family on the slopes of Mount Meru. A large bungalow, in a one hectare small-holding, yet this one had been painstakingly developed into an avian oasis. Once you were through the gate more than likely James would appear from the foliage with Swarovski binoculars and secateurs in hand, wearing a bush hat and cargo trousers, lamenting how ‘urban’ was this private jungle, lying as it still does, above the busy safari city of Arusha. A ‘sonic shamba’ he called it. And certainly the garden reverberated with the exotic song of over forty resident species of bird. Yet it is characteristic of the man that he has always yearned for wilder places in a place many would consider already wild.

James is a full-time naturalist, has been for over sixty years. He’s also an ecological philosopher. Wrestling with life’s contradictions; birds are both his delight and a potent symbol. They represent his own yearning to be utterly free “in nature”. As indicators of our environmental health, they embody our duty of concern for this living planet of which we are an inextricable part.

James’ professional guiding career began in 1988 with a Sunbird/Wings tour of Assam and Northern India. Since the mid 1960s his quest for the wild has taken him through Europe, across the Middle East, to the farthest corner of Russia and all around the bird-rich periphery of North America. In the 1980s and 90s he was a professional biological conservationist for lengthy periods in Thailand, on tiny Aride Island in the Seychelles, in Ethiopia, and in Laos. In 1995 he found his ‘soul-mate’ in Elsie MacRae and they ‘settled’ with two young sons in a remote forested corner of western Scotland. By the early 2000s he was studying migration, from a tiny blue cottage in Andalucia, overlooking a ‘migrant bottleneck’ at the Strait of Gibraltar. At the beginning of 2005, “as soon as the lads were old enough, only days after the Great Tsunami” he went to Tanzania, as a volunteer to help with the national waterbird survey, and a decision was made there and then to move the young family to tropical Africa, to Arusha.

James leads bird and wildlife trips and revels in the continued abundance and ubiquitousness of East Africa’s wildlife. As a result of the financial crisis, which curbed foreign travel for so many people, James returned to the ecological impact assessment business in West Africa, work he had previously undertaken in Europe and Asia. Four years observing the reality of “offsetting and mitigation“, in the global rush to grab Africa’s resources, was more than enough. So it was with an evident sense of relief that he recently returned to nature guiding, to writing and to “gardening” with, or perhaps we should say for Nature.

After sixty years travelling four continents, living as much as possible in nature, experiencing great doubts and contradictions whilst reflecting deeply, James tried to deliver a simple, but challenging, message. When, as a young boy in the booming 1960s he heard politicians and business men promising permanent economic growth, he was already asking “What future is there for wild nature?”

He describes the relationship between nature and our industrial age as ‘deeply antagonistic’. And he asks the awkward questions. The ones that make us think. “Should we not revere nature? Are we not an integral part of nature? How else can we ever live in harmony?“

“I seek, what you might call, an honest dialogue with Nature, the functioning system of planet Earth, of which we are all a part. How has it come to be that we allow our lands and seas, our living landscapes, our ecosystems to be brutally abused simply for short-term monetary gain? For financial profit, flashing digits in a computer screen, fake wealth, purchasing power, that goes to the tiny greedy few? To the spiritually and morally least worthy members of our crumbling societies? Healing ourselves is necessary if we are to help Earth heal this planet. Our planet has little need for financiers, their economics and the religion of profit (aka greed). Go and ask any ten year old student today! It has however a great deal to do with our regaining love and respect for “Nature”, regardless of our selfish desire for greater physical comfort and our runaway materialist expectations. So let us all – each and every one in our own small ways – start to widen our horizons and control our ‘programmed’ appetites. Starting right now

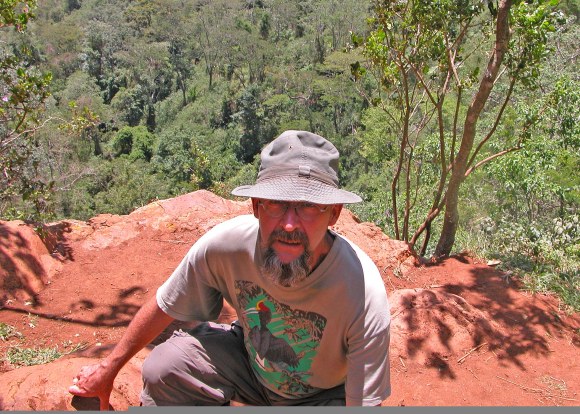

A picture of Ngurdoto Crater, when we first arrived in Arusha, perhaps something or is it someone, is not where she should be!

A picture of Ngurdoto Crater, when we first arrived in Arusha, perhaps something or is it someone, is not where she should be!